Editorial | ‘Fixing PERS is Job. 1 — and it’s doable’

Published 3:26 pm Wednesday, January 9, 2019

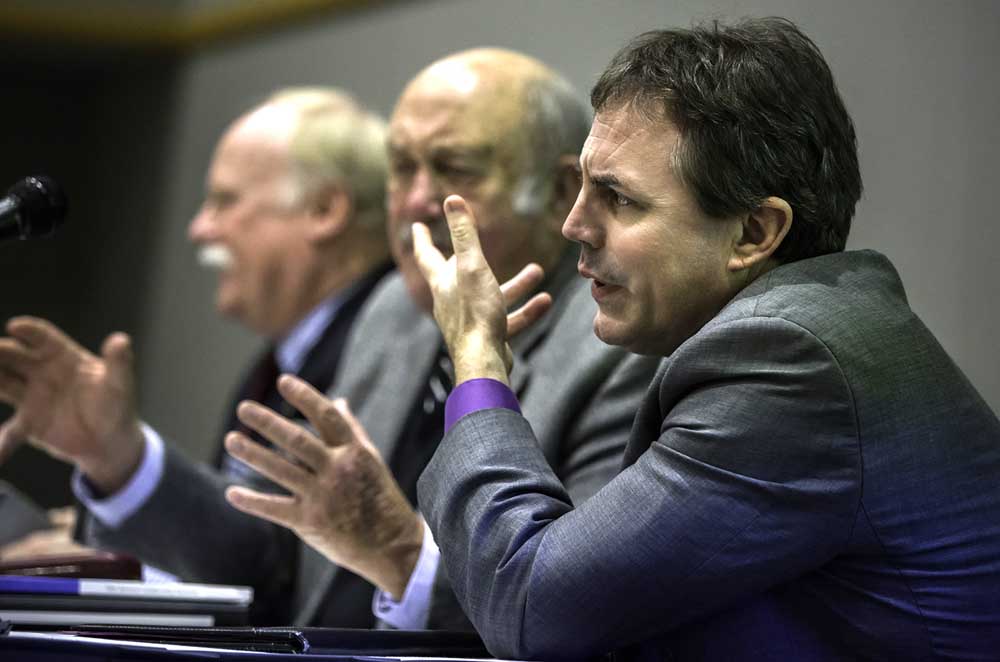

- Mark Mulvihill (right) fields questions after a 2015 presentation at the Oregon Leadership Summit at the Oregon Convention Center. Mulvihill, the superintendent of the InterMountain Education Service District, has proposed allowing pubic employees to draw a pension while working to help pay down PERS liability.

A new legislative report underscores that PERS could be headed for more trouble.

The report from the Legislative Fiscal Office reaffirms that the Oregon Public Employees Retirement System remains highly dependent on investment income for its financial stability. That is not a surprise. However, it should concern Oregon officials, especially in light of the current global economic swings.

Our federal leaders are not helping, with their trade disputes and partial government shutdown. Their lack of fiscal leadership and political cooperation adds to worries that the U.S. will fall into a recession. Where the nation goes economically, so goes Oregon.

The legislative report is based on a study last year from the Pew Charitable Trusts, which compared state pension plans for fiscal 2016. PERS had one of the worst ratios of operating cash flow.

On the other hand, PERS is one of the better-funded public pension plans. Cumulatively, state pension plans amassed a $1.4 trillion deficit, because they generally are paying more in benefits than they receive in pension contributions. Poor investment returns also are factors, although PERS has done relatively well.

So … PERS is not in danger of imminent insolvency, it is in better condition than many state funds but it is more subject to market volatility.

It should be of little comfort that PERS is not as bad off as other public pension funds. PERS’ unfunded actuarial liability forces schools and local governments to cut current jobs and services to pay for pensions. The burden can fall disproportionately on rural Oregon, as is detailed in the winter edition of The Other Oregon, a quarterly magazine from EO Media Group.

Rural Oregon also has proposed solutions. Mark Mulvihill, superintendent of the InterMountain Education Service District in Pendleton, has proposed changing state law to allow longtime public employees to collect both their pension and their salary for several years before retirement. Schools and government agencies would benefit from retaining good workers who were considering retiring, employees would have more money in the short term, and they and their employer would contribute 6 percent of their salary toward paying down the employer’s PERS liability.

The PERS burden is staggering, and it’s growing exponentially. For Clatskanie and Ontario — cities on opposite sides of the state — the burden is roughly the equivalent of six times the city’s annual payroll, according to 2017 figures from PERS.

That is why the Oregon Business Plan said in a report last month: “Fixing PERS is Job 1, and it’s doable.”

Among the plan’s recommendations: Oregon should again require that public employees contribute 6 percent of their pay to their pension, similar to what most states do. Oregon could move to a defined-contribution system, like a 401(k), for future employees. The state also could give current employees a choice of staying with PERS or switching to a 401(k).

All are solid ideas. All are reasonable. Only one thing is missing so far — leadership from Gov. Kate Brown and the Legislature.