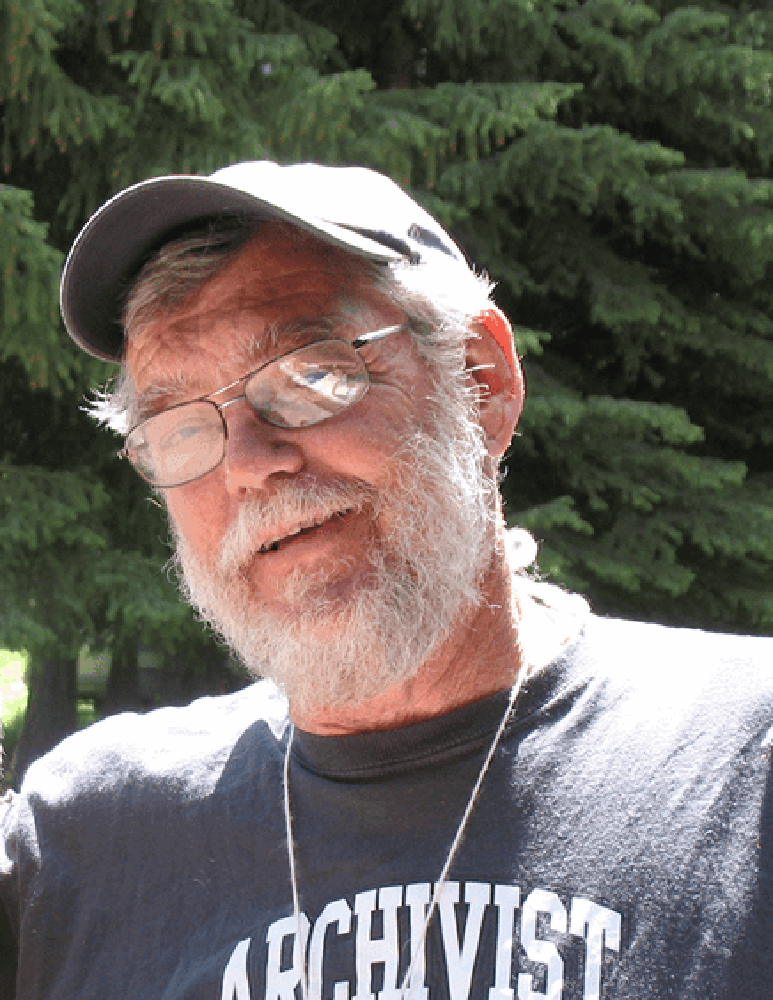

Rich Wandschneider: Let’s examine the nature of elections and citizenship

Published 9:15 pm Tuesday, November 5, 2024

- Rich Wandschneider

On Tuesday, Nov. 5, I popped out of bed early, started the coffee, lit the fire, and sat down to read. I read more of the same comments and editorial posts about Donald Trump’s total unsuitability for the presidency, about his flaming rhetoric and promised retributions. And I read about hope in Iowa, a pollster who had been right two times about Trump — about his winning in 2016 and his losing in 2020 — thought Iowa would vote Kamala Harris this time.

On Wednesday, I woke just as early, turned on the radio to get the rest of the story I’d gone to bed with just hours before. I soon turned the radio off and hunkered back under the comforting blankets. And stayed for a long time. It was hard to crawl out of bed, hard to make the coffee and do most of my morning chores and stretches — hard to find the enthusiasm for them.

Trending

And hard to read the morning opinions: Harris didn’t separate enough from Joe Biden; she didn’t present a whole picture of her intentions; Trump was protected by God and the Christians after being shot; Arab Americans went for Trump or not at all in disappointment with Biden-Harris actions on the Israeli war in Gaza, and more stories and opinions about Harris’s loss. The most striking one for me was “Stop Pretending Trump is Not Who We Are,” by Carlos Lozada in The New York Times. Lozada wrote:

“Throughout Trump’s life, he has embodied every national fascination: money and greed in the 1980s, sex scandals in the 1990s, reality television in the 2000s, social media in the 2010s. Why wouldn’t we deserve him now?”

He did forget to mention religion and the new Christian Nationalism. And none of above answered my pre-election question about those who chose not to — or found it too difficult to — vote. How is it that we can be a government of and for the people with a third of the eligible voters not voting? I took a brief stab at it then: the Native Americans who didn’t have street addresses; the homeless; those ill or disabled; the Democrats in Oregon and California who knew which way our states were going and thought their votes not needed; those in other states — much larger numbers — who didn’t think their vote would count, or who just didn’t give a damn.

The Greeks of old thought a democracy should be run by an elite of informed citizens. The Indians of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy — also known as the Iroquois Confederacy — who are credited with the example of representative government known to our nation’s founders, also depended on an informed population: women of each of the six tribes selected representative men, who sat together to solve disputes. It worked for some 3,000 years.

But the ancient Greeks and the Haudenosaunee of North America operated in much smaller arenas, where citizens in the hundreds and thousands knew each other well personally or by close following. And they did so before the tools of modern propaganda and electioneering were even ideas. The question is whether and how we can have an effective representative democracy in our times.

And, it seems to me that rather than analyzing the ideas that swung actual voters to one side or the other in this election, our pundits and academics might address the broader issue of educating the millions, and making them believe that their ideas and votes count. Many countries trying to practice democracy have voting holidays, and some countries, citing voting as a responsibility and a duty, have compulsory voting.

Trending

It’s hard to imagine our 70 or 80 million nonvoters — that’s actual numbers of eligible voters who sit elections out — complying with mandatory voting, or even to imagine our country developing a process to police such a policy. A voting holiday and rewards to voters — even the “I voted” stickers of old worked in this direction — might be easier to implement. Making the popular vote stronger or even replacing the Electoral College might encourage more voting.

The point is that a large number of our citizens are not engaged in the electoral process and, that among those who do vote, the impacts of lies, deception, and even foreign interference, must be considerable. I’m asking that we all examine the nature of elections and citizenship rather than continue to parse the reasons that the recent elections went one way or the other.

And then, to use Carlos Lozado’s words cited above, how do we make voting — and citizenship — “national fascinations”? I might add, “before we slide into autocracy,” as seems to be happening in many places in a world struggling with popular democracy.