Main Street: The year turns, local and simple

Published 6:30 am Thursday, January 11, 2024

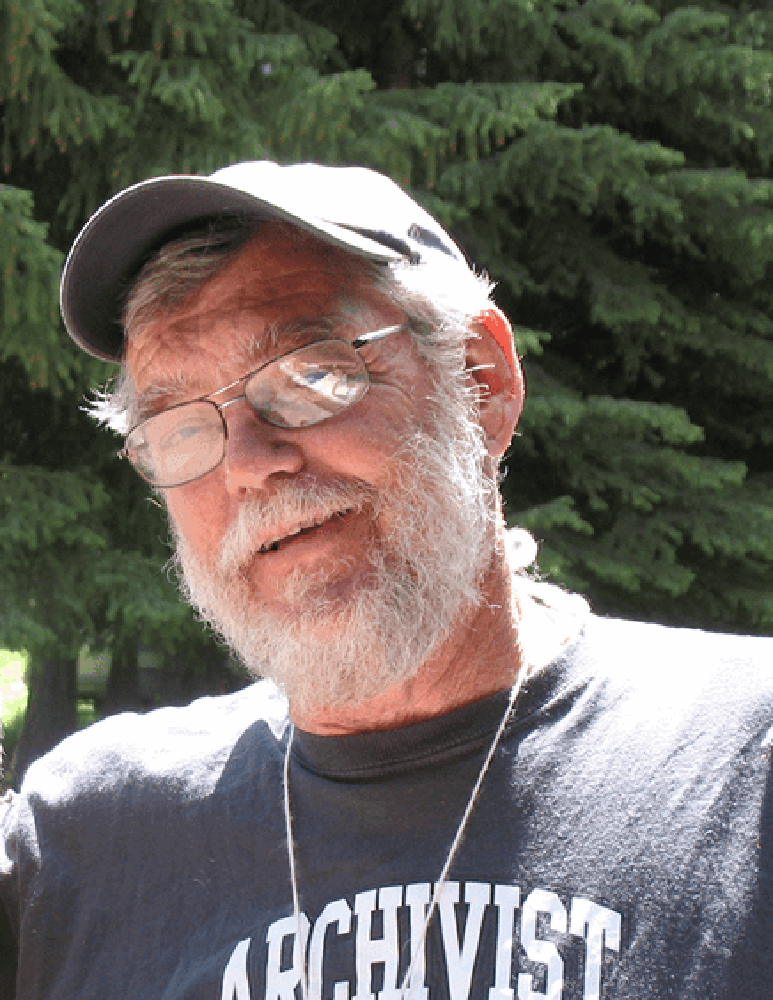

- Rich Wandschneider

The year 2023 rushed to its end for me, in fact almost ending it all with my rollover in the Wallowa River canyon at the end of November.

Then, testing my aging body, I went ahead with a scheduled knee replacement on Dec. 12. Friends who had been through this ordeal told me that the hip replacements I’d had years ago were cake walks, that knees are the real deal.

They were right. I don’t know how to describe the first two weeks, but they were brutal. Intense swelling, aches and pains that I’d not experienced before, being dependent on others for rides, wood chopping, and sympathy (thank you all)!

“Are you going to get the other knee done,” people ask. Like a new mom remembering childbirth, I say it’s too early to say.

At about the three-week mark, I started emerging out of this knee-netherworld and started feeling human. Walking without a walker, doing the physical therapy with the experts and on my own with some relish, being able to read more than a page or write more than a paragraph before losing it.

And here I am alive and mostly awake in 2024.

It’s a sobering time. I’m sobered by my recent experiences, and by the world I wake to — divisions across our country and conflicts across the world! Many of those conflicts are in places I knew and loved as a young man. The Middle East and Mediterranean have been rocked by earthquakes and fires, led by corrupt politicians, fractured by communal divisions, and murdered by outsiders’ misunderstandings and proxy wars. It’s hard to get a handle on where things have gone wrong, and on where and how humanity remains.

That’s the irony and the sadness of it. Yesterday Israeli and Palestinian children were killed in a school they attended together. Small patches of individuals and old and new peace-building organizations come to light when a journalist stumbles on them in Jerusalem or at Haifa University. A journalist in Gaza mourned his journalist son’s death, and continued to tell the story. United Nations Aid workers — more than 100 of them have been killed — continue to get food to hungry war survivors.

While I wait for a big hero, a Martin Luther King or Nelson Mandela, to emerge from the carnage and walk us to peaceful solutions, thousands of people are quietly addressing the world’s ills, making sure we know about those ills, and making things a bit better. My friend Steve, who doctored for years in the world’s hard places with Doctors Without Borders, said that their guiding principle was that a wounded person is no longer a combatant. And, I thought, students in the same school, Arab or Israeli, are still students. What beautiful simplicities.

Our local Fishtrap just finished a weekend conference they called “Can We Talk?” Outside specialists showed the differences between “debate” and “discussion,” and promoted “dialog.” Local leaders of nonprofits and churches stressed the problems of growth and misunderstanding, and the need to go back and talk to the individuals who we might have clashed with in public to find our common grounds. And to sort and address our differences.

The simple thing is that in a real community — and especially in a small one like ours — we all need and rely on each other. We’re all students, teachers, and wounded warriors together. The volunteer firefighters don’t ask for political or religious affiliation when they come to your house; the doctors and nurses don’t practice partisan medicine.

As part of Fishtrap’s weekend program, organizers asked Jacy Sohappy to talk about “intergenerational communication.” Jacy is enrolled on the Umatilla Reservation, and works there and for the Nez Perce Homeland in Wallowa. The talk started with fond memories of lessons and personalities of grandparents, but it soon became a description of tribal culture: the importance of elders and listening to elders; each “generation” of children, parents, and grandparents, who are all brothers and sisters, moms, dads, uncles and aunts in their cohort; the passing down of foods, religion, regalia, and culture from one generation to the next.

Jacy has allowed her mother and her mother’s and grandmother’s generations to help raise her daughter; sometimes parents are too busy making a living and grandparents are the perfect vehicles for practical and cultural knowledge. Jacy’s daughter is 18 and a coming Happy Canyon Princess. She’ll wear regalia from her mother, and from past generations.

At some time during Jacy’s talk, it occurred to me that we have spent over 300 years in this country trying to “assimilate” Indians. We’ve outlawed languages and religion, potlaches and dances. We’ve stolen children from parents, cut hair and washed Native words out of mouths with boarding school soap.

Indians have survived it all, and now willingly show us how We Can Talk.