Main Street: People move when they are hungry

Published 2:07 pm Wednesday, April 17, 2019

Or scared. My grandfather left Norway about 1900, when he was 18, following an older brother to America, because the farm had been broken up too many times and could no longer support the growing family. Years later, after my grandfather died, in Minnesota, I visited the farm in Norway. The youngest brother he’d never met, retired now, watched as his youngest son worked the farm; the rest of that generation too is scattered over Norway and America.

The Germans were the scared ones. My grandfather on that side was just two when his family made it to Minnesota in the late 1890s. From the 1840s on, right through the Civil War, Germans made up the largest share of American immigrants. Borders shifted, people moved and were moved by bigger powers, and men feared serving in the Kaiser’s army. They came to America, made sausages and beer in Milwaukee and St. Louis, farmed and started small businesses across the Midwest.

Trending

We’re taught that the earliest Anglo and European immigrants to America were fleeing religious persecution, but odds are that more of them were hungry. Over half who came before the founding were indentured servants, taken to the docks by their fathers, handed over to ships’ captains to be sold into servitude in America. Maybe the parents and remaining siblings would make it on diminished agricultural crops in a Europe cold with the Little Ice Age.

The Irish were hungry too when the potato blight hit and ruined their staple crop; millions fled to America; thousands filled the Catholic priesthood across the world.

Today, some 3 million Syrian refugees are in Turkey, a million or more in Jordan. Two or three times that many are internally displaced. We think of them as war refugees, and although that is likely the immediate cause, drought and hunger is what drove them from farms to Aleppo and Damascus where they looked for work and food and jumped in when demonstrators demanded political change. Odds are that the Arab Spring in Egypt and Tunisia and across the Middle East was fueled or inflamed by similar rural to urban pressures.

In Europe the refugees—and there are millions—are primarily from Africa. Families split up when drought and hunger comes, gather resources and send a few to seek relief in Europe and send remittances to Africa. And this is pretty much the situation at our southern border. Remittances have been important sources of income in Mexico and Central America for some time. The situation in Honduras now is probably the worst. The New York Times profiled coffee farmers there, and said yesterday that “gradually rising temperatures, more extreme weather events and increasingly unpredictable patterns — like rain not falling when it should, or pouring when it shouldn’t — have disrupted growing cycles and promoted the relentless spread of pests.”

“The obstacles have cut crop production or wiped out entire harvests, leaving already poor families destitute,” it continues. Look for coffee prices and refugee numbers to rise. We’re going to have to find a way to deal with it—it might be a way to fill places left by a shrinking population in many parts of the US.

Here’s where it gets interesting. The US right now is experiencing major internal dislocations, and if you watched the recent weather news from Nebraska, have followed the land loss into the Gulf in Louisiana and Florida, growing fire events in California, and this weekend’s tornados in Texas, we can expect some large movements of people within the country. The look on the Nebraska farmer’s face as he surveys dead cows on land inundated by flood is resignation—he says he’ll rebuild, but will his children take up the farm? The faces in flooded Texas and Louisiana and smoke-filled California are more terror than resignation. People are leaving.

Trending

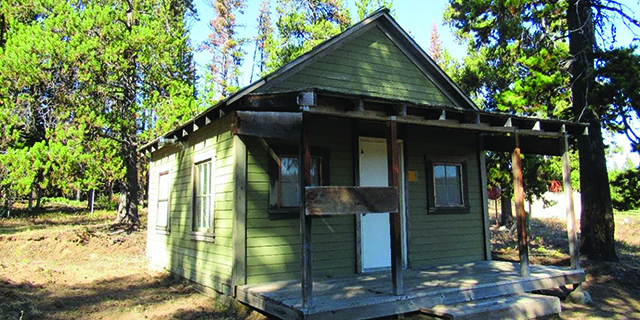

It won’t be the first time this has happened. Maybe some of you come from family that left Nebraska and Kansas during the dust bowl. I remember the face and story but not the name of an old man who told me in 1971 that he’d sold his farm and everything on it, bought a 1932 Chevy and drove till he ran out of gas and money in Lostine.

We’re not a nation of farmers now, as we were in the 1930s, but land and what happens on it is still crucial to food production—and to where we want to live. Hunger and fear more often have a job between them and the land. Still, agriculture will have to adjust with changes in cropping and manpower.

And Wallowa County will see real estate prices and populations rise as American refuges bring their savings, home equity, hammers, law degrees, and children to live in “safe” places like ours.