Snake River Chinook retain more ancestral genetics

Published 8:51 am Wednesday, January 24, 2018

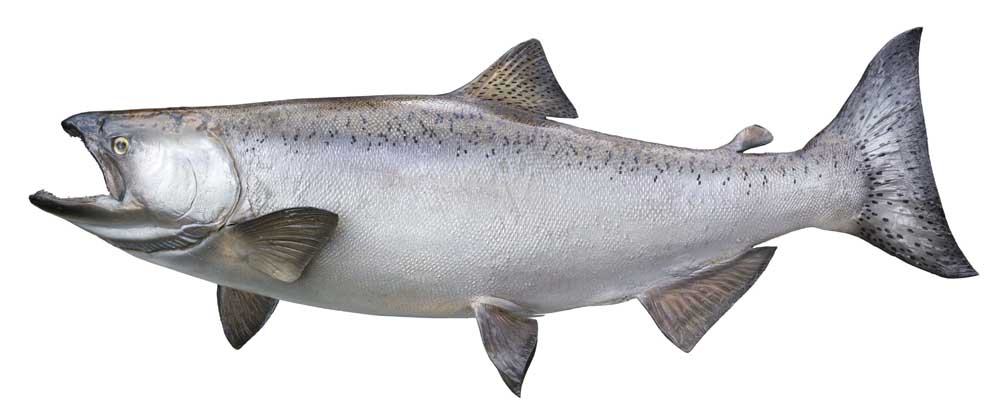

- A spring Chinook salmon, also known as an Alaskan king salmon.

Genetic diversity is essential to long-term adaptability and survival of any species. By that measure, upper Columbia River Chinook salmon are in deep trouble. A new study, published Jan. 10 finds that within the past century, the Chinook salmon in the upper Columbia River have lost almost 70 percent of their genetic variation.

But their Snake River cousins have lost only about 30 percent of their genetic variation, making Snake River Chinook a potentially more resilient fish.

Trending

Bobbi Johnson, a graduate student at Washington State University, compared the genetics (mostly mitochondrial DNA) from modern fish with fish remains found at Native American sites. The ancient samples came either from middens (places where encampments piled food waste and scraps) or were supplied to her by the Colville, Nez Perce and other tribes from their archival or heritage materials.

Her 346 ancient samples from the Columbia, Spokane and Snake Rivers included a 7,627-year-old salmon vertebrae found at an ancient fishing encampment site the Columbia at Kettle Falls, Wash. She also used 7,200-year-old fish remains from near Spokane Falls, and an estimated 2,500- to 5,000-year-old fish backbone from Granite Point on the Snake.

Younger samples included a 1,450-year-old site at Harder on the Snake, and a second, 1,150-year-old site near Kettle Falls. All of the ancient Columbia River samples came from sites above Grand Coolee Dam, which ended salmon runs in the 600 miles of main-stem river above it.

Johnson also analyzed fin clips of 379 contemporary Chinook from the Columbia, and Snake. Her results confirmed what biologists have long suspected: The genetic diversity of Chinook salmon has declined significantly.

The research revealed other things as well. Prior to European settlement, spring, summer and fall runs of Columbia River Chinook swan (and spawned in) the entire river. Today, the Columbia River Fall Chinook spawns only in Hanford Reach.

The samples from Spokane Falls came from six different lineages of Chinook. Today, Chinook are extinct in the Spokane River, blocked in 1911 by the construction of the Little Falls Dam. Their ancient DNA held far more genetic diversity than modern Chinook.

Trending

Most of Johnson’s study examined mitochondrial DNA. She and her partners in the study tallied details from the same segment of each fish’s genetic code.

Haplotypes (groups of genes passed down through generations) figured prominently, as did determination of nucleotide diversity (an estimate of overall genetic variation.)

While not a way of defining “sub-species,” this information shows how closely related different individuals are. Present-day Columbia River Chinook are sort of all married to their second cousins. More than 2/3 of their genetic diversity has vanished.

Genetic lineages that were present 1,000 years ago are absent today. In Snake River fish, the loss is less devastating. Only about 1/3 of the gene variations found in ancient samples are missing today.

The vanished gene sequences likely controlled a range of sometimes-subtle variations in physical appearance (size, color) to behaviors (the length of time at sea, the timing of return). Now lost, these variations cannot be recovered except through mutation or genetic drift.

Why the difference between Columbia and Snake River Chinook diversity? Johnson has a few ideas.

First, there’s the possible influence of pre-Contact Native American harvest. Both Snake River and Upper Columbia River fish would have been caught at about the same percentages at Celilo Falls.

But the Columbia River fish were subjected to another intense fishery at Kettle Falls. It’s estimated that the Colville tribe alone harvested almost 300,000 pounds of Chinook at Kettle Falls (on the Columbia) each year.

The Snake River system has no equivalent passage barrier/fishing opportunity. Fish bearing the full spectrum of genetic variation were able to navigate the Snake River and its tributaries to reach their spawning grounds.

Johnson also believes it likely that the Nez Perce and other tribes along the Snake included a greater diversity of other fish (sturgeon, suckers, pikeminnows), thus lowering their total catch of salmon and helping the Chinook retain a greater amount of genetic diversity. Ancient samples from the Snake river included these species of fish along with Chinook and other salmon.

Once Europeans arrived, they tended to target the large Chinook that were bound for the upper Columbia, thus further depleting the fish’s genetic pool. More contemporary factors in the loss of diversity include the introduction of millions of hatchery fish and the overall challenges of navigating today’s oceans.

Whatever the reasons, Snake River Chinook have retained a greater percentage of their genetic diversity than their upper Columbia cousins. They are, potentially, more resilient fish. And that is good news for us and for the fish.

LEARN MORE

news.wsu.edu/2018/01/10/chinook-salmon/

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0190059

Ellen Morris Bishop holds a doctorate in geology and specializes in the exotic terranes of the Northwest. Pacific Northwest landscapes –– their geologic history and ecosystems –– are her specialty.